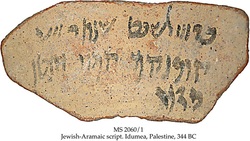

In his third lecture, entitled 'Levantine Epigraphy and Samaria, Judaea and Idumaea during the Achaemenid Period', Prof. Lemaire showed the vital importance of epigraphic material for the political and social history of the southern Levant in the Persian period, particularly in the 4th century BCE. My notes are less ordered, as the presentation was less structured within each discussed region.

PART I: SAMARIA

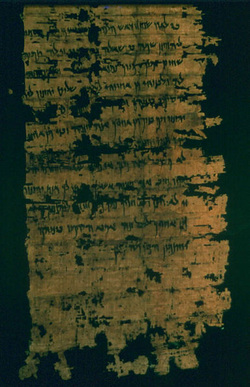

The documents and bullae from Wadi Daliyeh – widely referred to as Samaria documents – were recently re-edited by Jan Dušek, a very fine epigrapher (Les manuscrits araméens du Wadi Daliyeh et la Samarie vers 450-332 av. J.-C. [Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 30; Brill: Leiden; Boston], 2007; for the coins see Meshorer and Qedar). These documents shed light mainly on the last decades of Persian control of the area:

The names in the papyri attest to a mixed society (North-Arabic, Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic).

While names do not map religion 1:1 it is likely significant that 57% of names have a yahwistic theophoric element, with other deities attested only between 1-3% each.

The order of governors of Samaria in the Persian period is as follows:

This fits neatly with the depiction of Ezra's mission according to Neh 12, dated to 398 BCE

According to the available evidence, Samaria extended as far north in the Galilee as Yoqne'ām [on the basis of one Aramaic ostracon, unlike the Phoenician ostraca found further north. I find this particular argument less convincing. If the ostracon had been in Samarian Hebrew, or at least written in Palaeo-Hebrew letters, like the bullae and coins, I could understand it, but otherwise, the fact that the ostracon was written in Aramaic solely indicates that it was written in the Persian empire.

The Eastern border ws probably the Jordan

The Southwestern border of Samaria unclear. After the revolt of Sidon lands formerly controlled by Sidon may have been given to Samaria but this remains unclear.

PART I: SAMARIA

The documents and bullae from Wadi Daliyeh – widely referred to as Samaria documents – were recently re-edited by Jan Dušek, a very fine epigrapher (Les manuscrits araméens du Wadi Daliyeh et la Samarie vers 450-332 av. J.-C. [Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 30; Brill: Leiden; Boston], 2007; for the coins see Meshorer and Qedar). These documents shed light mainly on the last decades of Persian control of the area:

The names in the papyri attest to a mixed society (North-Arabic, Hebrew, Phoenician and Aramaic).

While names do not map religion 1:1 it is likely significant that 57% of names have a yahwistic theophoric element, with other deities attested only between 1-3% each.

The order of governors of Samaria in the Persian period is as follows:

- Sanballat I (from before 445 until about 410/407 BCE)

- Delayah (, son of Sanballat; ca. 410/407 - ca. 370 BCE)

- Shelemyah [Dušek does not agree with this]

- Ḥananyah / 'Ananya (ca. 354 BCE)

This fits neatly with the depiction of Ezra's mission according to Neh 12, dated to 398 BCE

According to the available evidence, Samaria extended as far north in the Galilee as Yoqne'ām [on the basis of one Aramaic ostracon, unlike the Phoenician ostraca found further north. I find this particular argument less convincing. If the ostracon had been in Samarian Hebrew, or at least written in Palaeo-Hebrew letters, like the bullae and coins, I could understand it, but otherwise, the fact that the ostracon was written in Aramaic solely indicates that it was written in the Persian empire.

The Eastern border ws probably the Jordan

The Southwestern border of Samaria unclear. After the revolt of Sidon lands formerly controlled by Sidon may have been given to Samaria but this remains unclear.

Part II: YEHUD

Yehud stamps indicate that the Northern border of Yehud was North of Mizpah and Bethel.

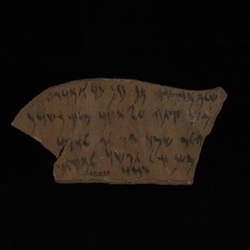

A problem for historians of the period is that to this date, not a single papyrus from this period was unearthed in Yehud, but there are a few ostraca, such as the Ketef Yeriho ostracon, found together with an Alexander coin, therefore dating both to the last third of the 4th century BCE. A few other ostraca were found in Jerusalem, Heshbon, En-Gedi

In general, several low-denomination coins have been found dated to the 4th century onwards

Lemaire speculated that Ezra mission and promulgation of the law may well have been contemporary with the fall of the Elephantine since the relation between Jerusalem and Elephantine seems to have been relatively good at the end of the 5th century BCE, and the Judean community in Elephantine seems to have been well informed who the important people were in Jerusalem.

We can identify the following governors of Yehud:

it is not impossible that these two were the only governors in the Persian 4th century

As high-priest we have a Yehohanan mentioned in the Elephantine letters, and a Yohanan in a coin which, according to Fried, should be dated to ca .370 BCE. Possibly, this Yohanan should be identified also with the Yohanan in Neh 12. This fits well with the presentation of governors of Samaria

The Hebrew Bible seems to know of two sets of boarders for Yehud, a small and a large one. The small one is attested, e.g. in Neh 3 and the larger Yehud mainly in Neh 11 (there extending south to Beer Sheva) .

Yehud stamps indicate that the Northern border of Yehud was North of Mizpah and Bethel.

A problem for historians of the period is that to this date, not a single papyrus from this period was unearthed in Yehud, but there are a few ostraca, such as the Ketef Yeriho ostracon, found together with an Alexander coin, therefore dating both to the last third of the 4th century BCE. A few other ostraca were found in Jerusalem, Heshbon, En-Gedi

In general, several low-denomination coins have been found dated to the 4th century onwards

Lemaire speculated that Ezra mission and promulgation of the law may well have been contemporary with the fall of the Elephantine since the relation between Jerusalem and Elephantine seems to have been relatively good at the end of the 5th century BCE, and the Judean community in Elephantine seems to have been well informed who the important people were in Jerusalem.

We can identify the following governors of Yehud:

- Bagavahya (Bagohi), ca. 407

- Yehizqiyah

it is not impossible that these two were the only governors in the Persian 4th century

As high-priest we have a Yehohanan mentioned in the Elephantine letters, and a Yohanan in a coin which, according to Fried, should be dated to ca .370 BCE. Possibly, this Yohanan should be identified also with the Yohanan in Neh 12. This fits well with the presentation of governors of Samaria

The Hebrew Bible seems to know of two sets of boarders for Yehud, a small and a large one. The small one is attested, e.g. in Neh 3 and the larger Yehud mainly in Neh 11 (there extending south to Beer Sheva) .

RSS Feed

RSS Feed