West Semitic Epigraphy and the Judean Diaspora during the Achaemenid Period: Babylonia, Egypt, Cyprus

Lemaire's second Schweich Lecture was a tour de force of epigraphic evidence for Judeans in the Near East in the Persian period. He started his lecture by referring to the cuneiform evidence that directly links to the Hebrew Bible and the exiles, such as the cuneiform tablet which shows that Nabû-šarussu-ukin (the Bible's Nebo-sarsekim) did exist and was a Babylonian Eunuch, the Weidner lists, the Murašû texts an the so-called āl-Yāhūdū texts. He gave a good summary of the currently available cuneiform evidence.

He then moved on to the Aramaic and – according to him at least in one case (one name is written as 'X ben Y' instead of 'X bar Y') – Hebrew dockets on cuneiform tablets.

According to him, in Babylonia, Jews demonstrably participated in three distinct cultures: Hebrew, Aramaic and Akkadian.

to me, this statement was the most problematic that Prof. Lemaire made during the entire presentations. None of the scribes writing the cuneiform evidence was Judean (according to their name), and one Hebrew name does not make fully 'Hebrew culture' (whatever that is). What we have evidence for is for the use of Aramaic to express either partly content or one of the people involved in the dockets. The distinctions may appear minor, but they are rather important, I believe.

He then moved on to the Aramaic and – according to him at least in one case (one name is written as 'X ben Y' instead of 'X bar Y') – Hebrew dockets on cuneiform tablets.

According to him, in Babylonia, Jews demonstrably participated in three distinct cultures: Hebrew, Aramaic and Akkadian.

to me, this statement was the most problematic that Prof. Lemaire made during the entire presentations. None of the scribes writing the cuneiform evidence was Judean (according to their name), and one Hebrew name does not make fully 'Hebrew culture' (whatever that is). What we have evidence for is for the use of Aramaic to express either partly content or one of the people involved in the dockets. The distinctions may appear minor, but they are rather important, I believe.

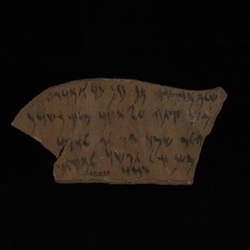

The second, and by far the longest part of the lecture, focussed on Elephantine. Not, as is so often the case only on the papyri from there, but mostly, in fact, on the ostraca of the Collection Claremont-Ganneau, recently published by Hélène Lozachmeur (2006). He argued that they are far closer to the everyday life than the papyri, and therefore are more representative of the Judean community's everyday life. He mentioned the use of the ostraca in indicating that the Aramaic documents in Ezra-Nehemiah are historically possible (the historian in me would ask, whether historical possibility is all that is needed for historical likelihood, but that is another question). He then went on to analyse the ostraca in particular with regard to the image of the religion of everyday Judean life in Elephantine and came to the result that the community's life was very much focussed around Yahu, and that other deities only appear very rarely indeed. Indeed, it seemed to Lemaire that the Judean community from Elephantine had a kind of 7th century Judean religiosity.

In an aside he then pointed to other sites of Judean activity in Egypt during the Persian period: Thebes, Abydos, Memphis, Saqqara, Daphne and Edfu.

The third and final part of the presentation concerned evidence for Judeans in Aramaic texts from elsewhere in the Persian empire, in particular two funerary inscriptions from Didaskaleion (which he thought were both unlikely), and then 5 funerary inscriptions from Cyprus which mention individuals with Judean names.

All in all a very interesting and useful summary of the currently available evidence for Judeans in Aramaic epigraphy in the Persian empire. Few know the texts as well as Lemaire.

In an aside he then pointed to other sites of Judean activity in Egypt during the Persian period: Thebes, Abydos, Memphis, Saqqara, Daphne and Edfu.

The third and final part of the presentation concerned evidence for Judeans in Aramaic texts from elsewhere in the Persian empire, in particular two funerary inscriptions from Didaskaleion (which he thought were both unlikely), and then 5 funerary inscriptions from Cyprus which mention individuals with Judean names.

All in all a very interesting and useful summary of the currently available evidence for Judeans in Aramaic epigraphy in the Persian empire. Few know the texts as well as Lemaire.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed